07 Feb The United States Spends Trillions on Healthcare – Where Does It Go?

The U.S. healthcare system is the most expensive in the world. Healthcare spending in the U.S. now exceeds $4.3B annually. This amount is staggering and requires a more detailed explanation. Where does it all go? How do we reduce the rising cost of care? Who is impacted, and at what cost?

Confronting the rising cost of healthcare is one of the key priorities in the Health Equity Guidelines letter signed by 50+ groups and delivered to the 118th Congress and Biden Administration. The letter states:

“To truly lower costs and achieve better outcomes for every patient, all healthcare stakeholders must be held accountable for the rising cost of care. Predatory practices such as surprise and unfair medical bills, exploitation of federal program loopholes, and rampant profiteering by middlemen in the drug supply chain must end. Rising out-of-pocket costs and the lack of competition in healthcare markets—particularly the growing concentration between insurers, hospitals, and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)—are also distressing trends that must be addressed. Increased government oversight and fundamental reforms are necessary to curb existing waste, fraud, and abuse and lower costs for every patient.”

HEC has long written about drivers of the rising healthcare costs as well as the impacts on diverse communities.

And just last month, HEC released a white paper titled “Putting Profits Over Patients: How the Corporatization of American Healthcare is Impacting Diverse Communities.” The paper cites:

Over the past three decades, the American healthcare system has evolved into a complex maze of large corporate conglomerates and bureaucratic processes, placing increased strain on the doctor-patient relationship. Hospital mergers have failed to deliver the promised benefits, and patient-focused care has given way to more impersonal and costly treatments as insurance companies have increasingly influenced doctors’ day-to-day decisions. Costs have risen and the quality of care has declined. Diverse communities are at the most significant risk from these negative trends…

…The corporate healthcare model, as currently structured, has failed. It has especially failed vulnerable populations who lack the means to access and pay for ever more expensive services and treatments. The harm to vulnerable populations has been particularly acute in five areas: insurance and hospital consolidation, rising costs, quality of coverage and care, administrative bureaucracy, and price transparency.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) estimate that healthcare costs have more than quintupled since 1990, even as consolidation in the healthcare system promised to reduce costs. CMS projects healthcare spending to reach $6.2 trillion in 2028. Experts predict out-of-pocket expenses will rise 10 percent per year through 2026. Yet for all this spending (the OECD estimates the per capita cost of healthcare in the U.S. is almost double that of most industrialized countries), the U.S. does not have “discernably better” health outcomes. Instead, there is a system where doctor-patient relationships do not come first, access to drugs and treatments is too often limited or nonexistent, patient costs are skyrocketing, and programs for underserved communities have veered from their mission.

In 2024, employers face the largest healthcare costs increases in more than a decade. Employer healthcare rose by 5.4% – 8.5% and these costs are likely to be passed on to employees. Increases in health insurance costs for employers are felt most severely by low-income workers. The Center for American Progress noted in late 2022:

[T]he burden tends to be greater for lower-income workers: Firms with a greater number of low-wage employees on average contribute 10 percent less toward single coverage premiums and 13 percent less to family coverage premiums than those with fewer low-wage employees. As premiums rise, the cost of health insurance grows as a share of total compensation, cutting into employees’ take home pay.

The rising cost of healthcare in the U.S. translates into higher insurance costs, under-resourced hospitals, and a lack of quality healthcare access for marginalized communities. Three in ten dollars spent on healthcare go toward administrative overhead. One in ten is the cost of fraud, fifty times more than is spent on fraud prevention.

To improve healthcare access and lower costs for underserved and minority communities, policymakers must pay closer attention to what’s actually driving the cost of healthcare.

In July 2023, the Peter G. Peterson Foundation reported:

The United States has one of the highest costs of healthcare in the world. In 2021, U.S. healthcare spending reached $4.3 trillion, which averages to about $12,900 per person. By comparison, the average cost of healthcare per person in other wealthy countries is only about half as much. While the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the trend in rising healthcare costs, such spending has been increasing long before COVID-19 began. Relative to the size of the economy, healthcare costs have increased over the past few decades, from 5 percent of GDP in 1960 to 18 percent in 2021.

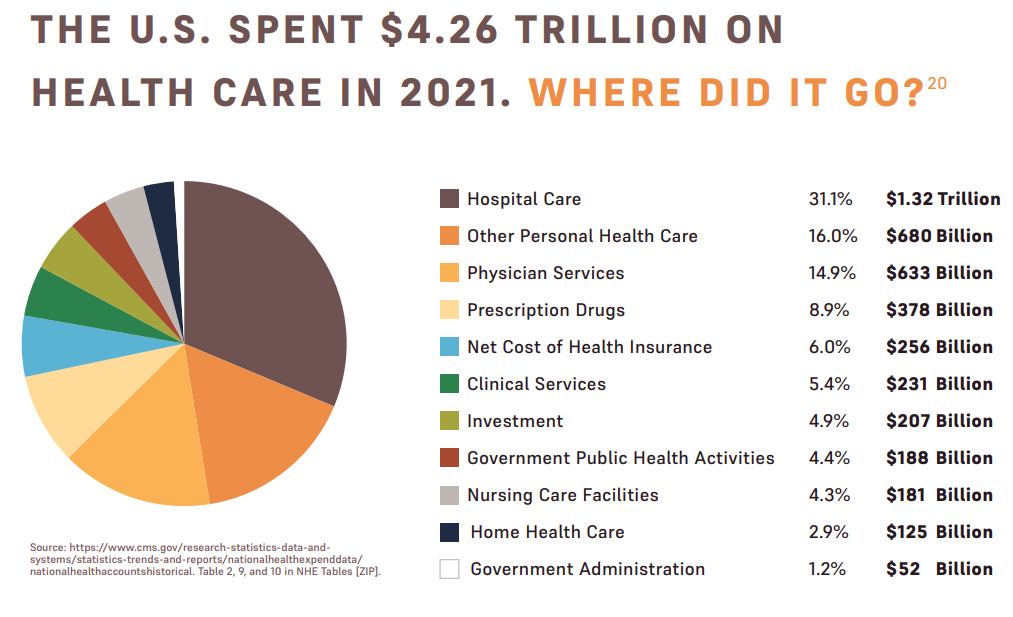

When it comes to lowering costs, prescription drug prices have become a focal point for lawmakers and political leaders, and it’s certainly true that growing drug prices contribute to those costs, however the data makes clear that drug prices are not the primary driver of increased costs.

Hospital care — the largest source of spending — totaled $1.32 trillion, or 31.1 percent of overall healthcare spending. Physician services cost $633.4 billion, or 14.9 percent of the total. And “other personal health care” costs represented $680.4 billion, or 16 percent of total spending. Prescription drugs accounted for just $378 billion, or less than nine percent, of the total $4.26 trillion spend on healthcare.

Addressing healthcare cost drivers is complex and can’t be achieved without close attention to data. To advance health equity, we must ensure that our policy efforts are well targeted and not misguided.

As an example of a misguided effort to lower the cost of healthcare – included in a past blog by HEC – tells of how Congressional attempts to lower drug prices could have impacted underserved communities. The legislation included a proposed potential prescription drug cost-saving measure called foreign reference pricing.

Foreign reference pricing essentially caps the cost the U.S. government would pay for certain prescription drugs based on the price another country is paying for the same drug. In practice, this allows the U.S. government to rely on arbitrary value judgments made by other foreign governments to set prices. It’s worth recognizing, the countries selected for the proposed pricing model have significantly smaller underserved and underrepresented communities than the United States.

Additionally, in these “reference” countries, foreign government officials often make coverage and payment decisions based on inherently flawed cost-benefit analyses, known as “quality-adjusted life-year” (QALY’s). QALY’s are an economic evaluation to measure disease burden, including both the quality and the quantity of life lived, which systematically devalues disadvantaged populations, particularly minorities and patients who are sick or disabled. Using this metric, governments and insurers may determine a given drug isn’t worth paying for based on the long-term health benefits of the patient. Opening the door to reference pricing would effectively endorse the use of discriminatory cost-effectiveness standards in the United States. Under this proposal, vulnerable patients would indirectly be subjected to biased QALY assessments.

Can Congress guarantee that importing healthcare models from largely homogenous countries with significantly smaller minority populations will hurt or help underserved communities in the U.S.? Is it possible such legislation will diminish access and availability of medicines for our underserved communities? If we are committed to achieving more equitable health outcomes, such questions must be addressed.

Congress should be commended for their commitment to address the rising cost of healthcare in the United States, and equally commended for recognizing all the factors — beyond just drugs — that are driving up healthcare as they craft legislative solutions.

We look forward to engaging with lawmakers as they seek additional strategic and sensible solutions to lower healthcare costs. With our communities in mind, we are committed to making progress.